After ChatGPT pushed generative AI into the public spotlight at the end of 2022, changes in the investment sector accelerated. The level of investment in AI hardware and data centers by companies has approached some of the largest investment waves in U.S. history. The market has consequently thrown out a bunch of attractive revenue curves, but the problem has also become sharper: how likely are these forecasts to be realized, and is it worth investing capital and time for them?

Michael J. Mauboussin from Morgan Stanley Investment Management’s Counterpoint Global directly provided a methodology in his report on the 10th: to evaluate such forward-looking judgments, one should “start with an initial belief and update that belief as new results appear,” which is essentially “Bayesian reasoning”: “New Conclusion = Initial Belief (Prior Probability) × Adjustment Factor from New Evidence (Likelihood Ratio).”

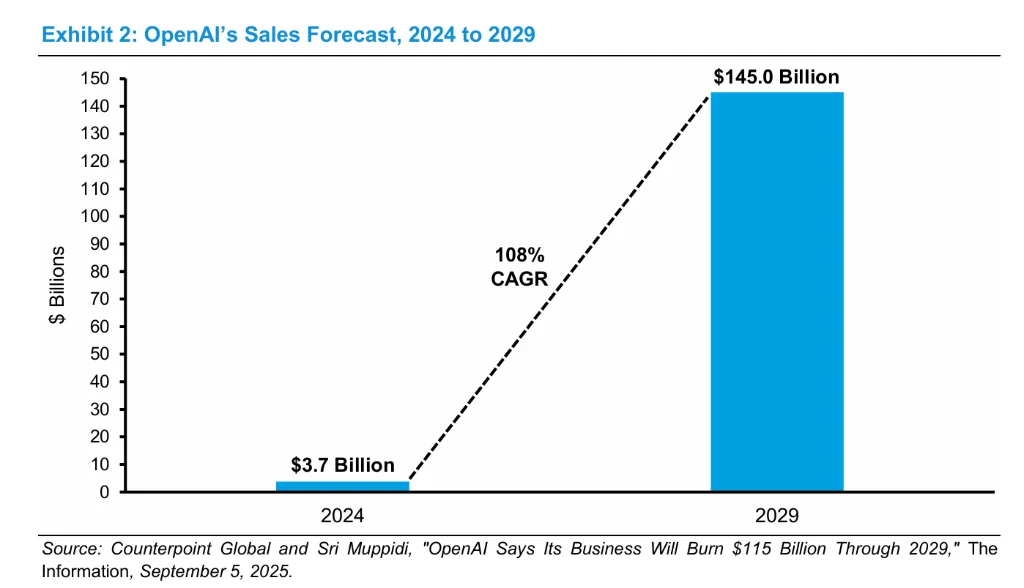

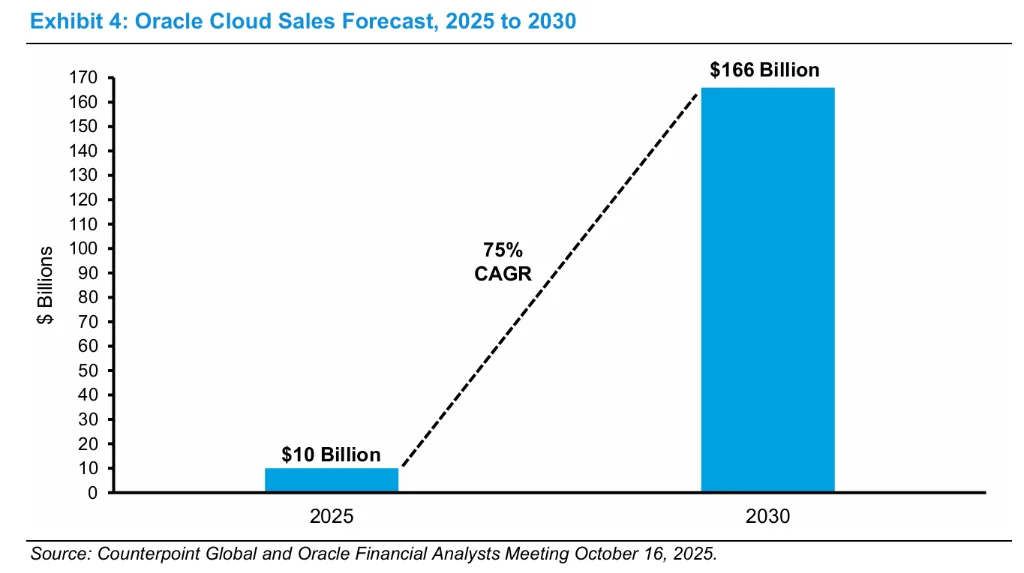

Following this framework, the report compared two of the most watched predictions to historical distributions: OpenAI’s revenue from $3.7 billion in 2024 to $145 billion in 2029 (a 108% compound annual growth rate over five years), and Oracle’s cloud business from $10 billion in fiscal year 2025 to $166 billion in fiscal year 2030 (a 75% five-year compound growth rate). The conclusion was blunt: among U.S. public companies between 1950-2024, no company has ever achieved this kind of scale growth from such starting points.

What’s more troublesome is that AI infrastructure is not as simple as “buying a few more servers.” Building data centers is essentially a large-scale project, and large projects have their own baseline failure rates: budget overruns, delays, and underperformance are almost the norm. The report also explained this series of intensive transactions and “capacity expansion announcements” as part of a competitive strategy: they may not just be aimed at meeting demand but also signaling to competitors, trying to deter potential entrants—but this kind of first-mover bet inherently carries high risk.

Putting OpenAI’s Forecast into Historical Context: 108% Compound Growth is “Blank” in the Sample

The report uses a very specific reference frame: it selects a group of U.S. listed companies from 1950-2024 whose initial revenue was between $2 billion and $5 billion (in 2024 dollars), with nearly 18,900 company-period observations. The mean five-year compound growth rate for this group was only 7.0%, with a standard deviation of 10.6%.

OpenAI’s forecast suggests: from $3.7 billion in 2024 to $145 billion in 2029, a 108% five-year compound growth rate. The report’s conclusion is tough—over the past three-quarters of a century, no publicly listed company has achieved such a pace. Even using a normal approximation to describe this, it’s nearly a 9.5 standard deviation result, with an extremely low probability. Furthermore, the historical growth distribution itself is not normal and has fat tails, but this doesn’t change the “almost invisible” conclusion.

A detail worth noting: since the sample has “never happened,” the baseline probability becomes 0, making Bayesian reasoning itself unworkable. The report uses common heuristic methods (such as 3/N, Laplace smoothing) to get an initial probability still under one-thousandth.

Evidence Does Help “Raise the Probability,” But to What Extent? The Report Doesn’t Make It Optimistic

The report acknowledges that baseline probabilities are not absolute laws and that the world will change. It provides two pieces of evidence that can push OpenAI’s probability of success upward:

- Speed of Diffusion: ChatGPT reached 100 million users in 2 months. In comparison, TikTok took 9 months, Instagram took 28 months, Facebook took 4.5 years; the internet took 7 years, mobile phones took 16 years, and telephones took 75 years. Even considering population changes, this speed is still extremely rare. The report also reminds us that users don’t necessarily equate to revenue, as many don’t pay.

- Short-Term Revenue Growth: OpenAI expects $13 billion in revenue in 2025, a year-over-year growth rate of about 250%. This is much higher than the average compound growth rate over five years.

However, the report immediately sets the “optimistic boundary”: the larger a company gets, the smaller the fluctuations in its growth rate tend to be, and sustaining a high growth rate becomes increasingly difficult. Furthermore, OpenAI also gave a 2030 revenue forecast of $200 billion, which means even with the window shifted, the 2025-2030 five-year compound growth rate is still projected to be 72.7%.

Using a reference group with initial revenue between $10 billion and $15 billion (about 3,700 observations), the conclusion remains the same: no one has ever done this. Even if the starting revenue threshold is lowered to at least $6.5 billion and the sample size expanded to more than 16,400 observations, the result is still the same.

Growth Doesn’t Equal Value: Cash Flow Gaps and Equity Incentives Will Pull the “High Growth Story” Back to Financial Reality

At this point, the report pivots to a more realistic reminder: growth itself doesn’t create value. It also introduces constraints in defining the “Total Addressable Market (TAM)”—it’s not just about “how much can be sold,” but “how much revenue can be generated with 100% market share under the condition of creating shareholder value.” The core constraint is whether the return on investment exceeds the cost of capital.

In OpenAI’s case, the report directly addresses the constraints:

- Free cash flow is expected to be negative $9 billion in 2025, and negative $17 billion in 2026. In this situation, maintaining “high-speed expansion + heavy investment” will almost inevitably require continued external financing.

- A significant portion of employee compensation is stock-based (SBC). It’s estimated that SBC will exceed income by 45% in 2025, equivalent to about $1.5 million per employee per year, and is seven times the SBC issuance intensity of large tech companies before their IPO.

These details don’t directly negate the revenue forecasts but push an often-overlooked problem to the forefront: even if the revenue growth materializes, the capital structure, financing conditions, and dilution costs could ultimately determine “what shareholders actually get.”

Oracle’s $166 Billion Target for Cloud: Signed Deals Are an Advantage, But Delivery and Financing Are Hard Constraints

Oracle’s narrative comes from a different set of evidence: the company signed several billion-dollar-level cloud infrastructure contracts in 2025, significantly boosting its “Remaining Performance Obligations” (RPO)—future revenue tied to signed customer agreements. Management therefore forecasted cloud revenue from $10 billion in fiscal 2025 to $166 billion in fiscal 2030, corresponding to a 75% five-year compound growth rate. In fiscal 2025, cloud will account for 17% of Oracle’s total revenue of $57.4 billion.

Again, the report starts by applying baseline probabilities: in the past 75 years, no company with starting revenue above $10 billion has managed to achieve this kind of growth in five years. Even lowering the starting revenue threshold to $5.6 billion, the conclusion is still the same.

It also provides a more directly comparable group to Oracle’s cloud size: companies with initial revenue between $8 billion and $12 billion, about 4,400 observations. The average five-year compound growth rate for this group was 5.7%, with a standard deviation of 9.6%. The report also reminds that this is comparing “business units” to “whole companies,” so it’s not an exact match.

Oracle’s advantage lies in its RPO scale, which can adjust the baseline probability, but the report emphasizes that the adjustment should not just consider orders, but also the financing needs to support growth, the risk from competitors, and the potential delays in infrastructure delivery.

AI Data Centers Are a Typical “Large Project,” and the Success Rate for Such Projects Doesn’t Favor You

The main battleground for AI investments is hardware and data centers. The report mentions that OpenAI and Oracle are both partners in the “Stargate Project,” which is expected to invest up to $500 billion in AI infrastructure by 2029.

The key point is: AI data centers differ from traditional data centers. They have more expensive hardware, significantly higher electricity demands, and more reliance on cooling systems. The bottlenecks are very real—electricity access, specialized hardware supply, and so on.

The report uses Bent Flyvbjerg’s database of 16,000 large projects for comparison. The results are almost “discouraging”:

- 47.9% of projects are completed within the budget.

- Only 8.5% are completed within budget and on time.

- Only 0.5% are completed within budget, on time, and achieve expected returns.

The takeaway is straightforward: don’t assume that “on-time delivery” is the default. Key bottlenecks like power, chips, and equipment need to be closely monitored. Meanwhile, modular design tends to succeed more easily, but in an environment of rapidly growing AI demand and competitors fighting for first-mover advantage, “slow thinking, fast action” is hard to execute.

Intensive Deals and Capacity Expansion Announcements Might Be a “First-Mover Deterrent” Competitive Experiment

The report counts that OpenAI announced about 15 transactions related to infrastructure construction in 2025. At the same time, giant cloud providers like Alphabet, Amazon, and Microsoft raised their capital expenditure forecasts, while players like Anthropic and CoreWeave made large investment commitments.

The author compares this frenzy with historical examples, such as the telecommunications investment wave from the late 90s to early 2000s, which eventually left behind overcapacity and bankruptcy cases. Today, there is still a “demand has not reached the ceiling” aspect—the report quotes data that shows, by the second half of 2025, the global AI diffusion rate (the percentage of people who have used GenAI products) is only 16%.

What’s truly interesting is the speculation on motivations: part of this action may be driven by a strategic signal—using large-scale capacity commitments to lock in the market and deter competitors and potential entrants. The report cites Porter’s concept of a “preemptive strategy” and also clearly spells out the risks: this is a bet on a market outcome that hasn’t yet clarified, and if it fails to scare off competitors, it could lead to a more intense war of attrition. A more realistic division is financing ability: early-stage AI companies need continuous external funding, while giants like Amazon, Google (NASDAQ:GOOGL), and Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META) have far more abundant cash flow and much higher tolerance for risk.

Through 2025, capital is still flowing, but the report clearly says: this will change.

What This Report Really Wants You to Do: Break the Story Into Probabilities and Update It with Data

The report repeatedly stresses that it is not “bearish on AI” but rather advocates turning the judgment process into an updatable probability problem: first set thresholds for the fervor using baseline probabilities, then slowly adjust using diffusion speed, real revenue, engineering progress, and financing conditions. It also emphasizes that it does not provide investment advice—however, it offers a starting point that is harder to deceive oneself with: when predictions fall into areas that have never appeared in historical samples, optimism itself needs evidence, and the evidence needs to be continuously updated.